If you've written a lot of code, you already know this truth: sometimes, we give way too much control to our components. Not because we're bad developers or don't understand abstraction, but because in our attempt to make things "reusable," we accidentally create components that seize behavior instead of hosting it.

Most systems break not because the logic is wrong, but because the control is in the wrong place. Let me show you what I mean with a painfully familiar example.

<DataTable

fetchUrl="/api/users"

enableSearch

enableFiltering

enableSorting

enablePagination

enableCSVExport

filters={[...]}

defaultSort="name"

onRowSelect={()=> {}}

onRowExpand={()=> {}}

pageSize={20}

debounceMs={300}

retryOnFail

rowVariant="striped"

selectableRows

expandableRows

customCellRenderer={fn}

errorRenderer={fn}

emptyRenderer={fn}

loadingRenderer={fn}

// ...plus 20 more options

/>You've seen this happen: functions that decide how to fetch, classes that create their own dependencies, components that choose API endpoints, utilities that hard-code logic, and widgets that "think" they own the business rules. Every time a module takes ownership of behavior that should be supplied from outside, it grows tighter, heavier, and harder to reuse.

The above example isn't a DataTable problem—it's a control problem. This is where Inversion of Control (IoC) comes to shine.

What is Inversion of Control

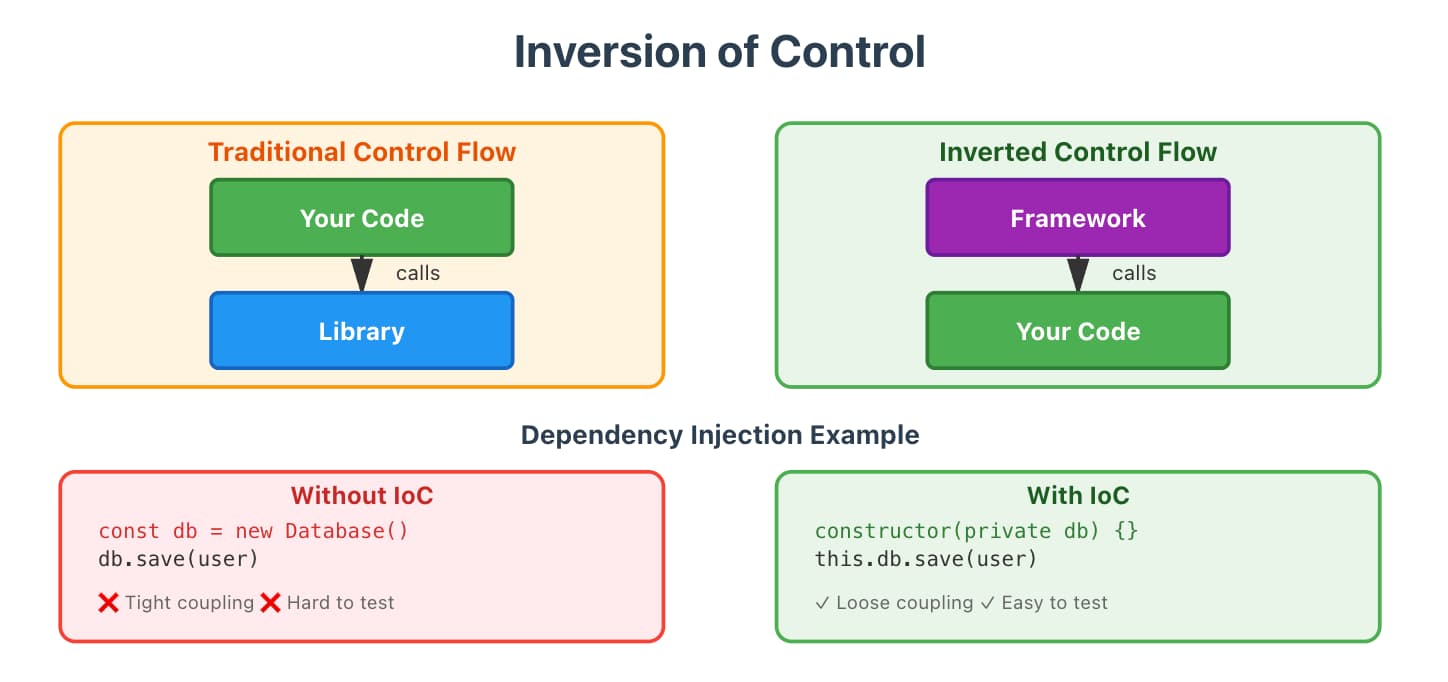

Inversion of Control (IoC) isn't a pattern, a library, or a framework trick. It's a design philosophy: the provider controls the lifecycle; the consumer controls the behavior. Instead of components deciding the rules, they host the rules supplied by their parent.

Without IoC

Without IoC, the DataTable decides how to fetch, how to sort, how to filter, how to transform rows, how to debounce, how to paginate, and when to run all these. It owns the entire flow—fetching, sorting, filtering, debouncing, pagination, render logic, error handling, row transformation, and everything else. The component owns ALL the logic. Here's what that looks like:

// BLOATED DATATABLE (TOO MUCH CONTROL)

export function DataTable(props) {

const {

fetchUrl,

enableSearch,

enableFiltering,

enableSorting,

enablePagination,

filters,

defaultSort,

pageSize,

} = props;

const [rows, setRows] = useState([]);

const [search, setSearch] = useState("");

const [sort, setSort] = useState(defaultSort);

const [page, setPage] = useState(1);

useEffect(() => {

fetch(fetchUrl)

.then((r) => r.json())

.then((data) => {

let result = data;

if (enableSorting) result = sortRows(result, sort);

if (enableFiltering) result = filterRows(result, filters);

if (enableSearch) result = searchRows(result, search);

if (enablePagination) result = paginate(result, page, pageSize);

setRows(result);

});

}, [fetchUrl, search, sort, page, filters]);

return <table>{/* ... */}</table>;

}With IoC

With IoC, the DataTable decides only when sorting should trigger, when filtering should trigger, when pagination should advance, and when rows should be rendered. But the user injects the behaviors: fetch logic, sorting logic, filtering logic, transformation logic, and cell rendering logic. The behavior is injected, and the lifecycle is controlled.

Behavior flows downward from the parent, while lifecycle flows upward from the component. Let's rewrite the DataTable using IoC principles—we remove all behavior from the table and keep only lifecycle and rendering.

// IOC TABLE (LEAN, FLEXIBLE)

type TableProps<T> = {

rows: T[];

sort: SortState;

onSortChange: (s: SortState) => void;

filters: FilterState;

onFilterChange: (f: FilterState) => void;

children: React.ReactNode;

};

export function Table<T>({

rows,

sort,

onSortChange,

filters,

onFilterChange,

children,

}: TableProps<T>) {

return (

<>

<SortControls value={sort} onChange={onSortChange} />

<FilterControls value={filters} onChange={onFilterChange} />

<table>

{children}

<tbody>

{rows.map((r, i) => (

<tr key={i}>{/* table only renders */}</tr>

))}

</tbody>

</table>

</>

);

}The table no longer fetches, filters, sorts, paginates, transforms, searches, or debounces. It simply orchestrates the lifecycle: "Sorting changed—parent, do something." "Filtering changed—parent, do something." "Render these rows." Everything else lives in the parent.

Parent Now Controls Behavior

function UsersPage() {

const [sort, setSort] = useState({ column: "name", direction: "asc" });

const [filters, setFilters] = useState({ status: "active" });

const rows = useUserQuery({ sort, filters }); // ← consumer decides behavior

return (

<Table

rows={rows}

sort={sort}

onSortChange={setSort}

filters={filters}

onFilterChange={setFilters}

>

<Table.Column title="Name" render={(user)=> user.name} />

<Table.Column title="Email" render={(user)=> user.email} />

</Table>

);

}Now the table doesn't care if rows come from REST, GraphQL, tRPC, localStorage, IndexedDB, mock data, a cache, server components, or a streaming API. The behavior is injected, and the lifecycle is owned. This is Inversion of Control.

Conclusion

This was never about building the "perfect" DataTable. It was about control and why giving components too much of it always backfires. Once I started using Inversion of Control, my components instantly became lighter, easier to reuse, and way less stressful to maintain. The magic is simple: let the component handle when, and let you decide how.

That's the shift. Stop letting components own your logic. Start letting them host it. Your future self and your entire codebase will thank you.